Leonard Crosby January 16, 2024

Outside of writing and reading science fiction, teaching composition, and spending time with my family, I occasionally relax. Sometimes, I’ll spend that time playing video games. One of my favorites (which I rediscovered last year, after my wife bought me a Super Nintendo emulator for Christmas) is Final Fantasy VI. I played this as a teenager, but this time around, not remembering much of the game, I found a walkthrough to discover all its secrets. This lead me to Caves of Narshe, and a whole community of players obsessed with the game.

Caves of Narshe is a fan and walkthrough site for the first ten games of Squaresoft’s Final Fantasy series. According to its about page, “The Caves of Narshe was set up by Josh Alvies, a.k.a. Rangers51/R51 as a Final Fantasy VI website, on 31 July 1997.” Because Final Fantasy VI was the first part of the website, I’ll focus on it for my analysis, as provides the most detail into this unique online group.

For those who don’t know, Final Fantasy VI (also known as Final Fantasy III from its initial North American release) is a 1994 fantasy role-playing video game developed and published by SquareSoft for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. The game’s themes of a rebellion against an immoral military dictatorship, pursuit of a magical arms race, and depictions of an apocalyptic confrontation between good and evil, were groundbreaking compared to other games of the time, and earlier ones in the franchise. Final Fantasy VI received widespread critical acclaim, particularly for its graphics, soundtrack, story, characters, and setting. It is widely considered to be one of the greatest video games ever made and is often cited as a watershed title for the role-playing genre.

Due to how long Caves of Narshe has been up, and the amount of detail it provides, it appears to be one of the main websites on the series of games. On an average day, between 200-300 users are active on the site, and there are thousands of posts on its forums and message boards. For example, a screenshot from January 15, 2025:

Or one of the websites’ list of forum topics and comments:

To better understand this community, I’ll be using linguist John Swales’ concept of a “discourse community” outlined in his book, Genre Analysis. In the second chapter, “The Concept of Discourse Community,” he argues that humans create unique linguistic communities, which he calls “discourse communities” if they fit six criteria: they have broad public common goals, they have methods of intercommunication and participatory mechanisms among members to provide information and feedback, they use unique genres and lexis in their communications, and they have a mix of members with experience in the discourse. These are often hobby or fan groups, but they can take other forms. Caves of Narshe fits Swale’s discourse community definition perfectly.

First, it has a clear public goals: to share knowledge and fandom about the game:

The group’s modes of intercommunication and participatory mechanisms to provide this information and feedback to members are the walkthroughs themselves, but primarily the forums. Here we see members sharing information about the game, or updates on new versions or discoveries:

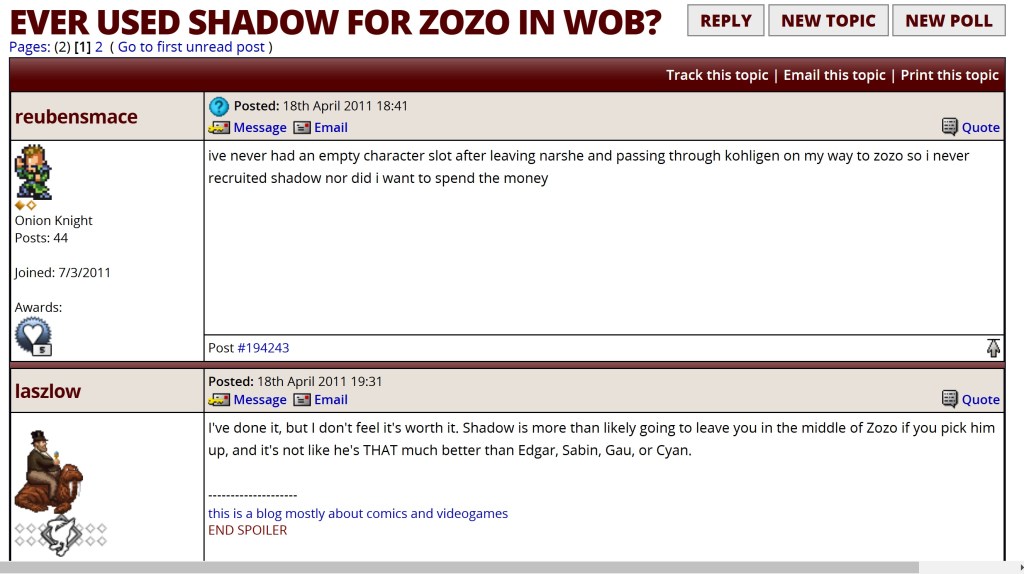

If we look through the forums carefully, we see that this community is only 200-300 members strong, and regularly changing, outside of a few leaders like the website owner himself. In this forums we also get a clear description of the genre of these communications. It usually occurs via text, but they’re accompanied by avatars (often characters from Final Fantasy VI, as in the above example) or gifs. Each member avatar comes with a join date, and icons to represent status (below the avatar) informing members of the level of expertise of the person they are talking to. Note, for example, the early join date of Rangers51, the founder of the website (with 29 awards), vs. the much later join date of Reubensmace and the single award.

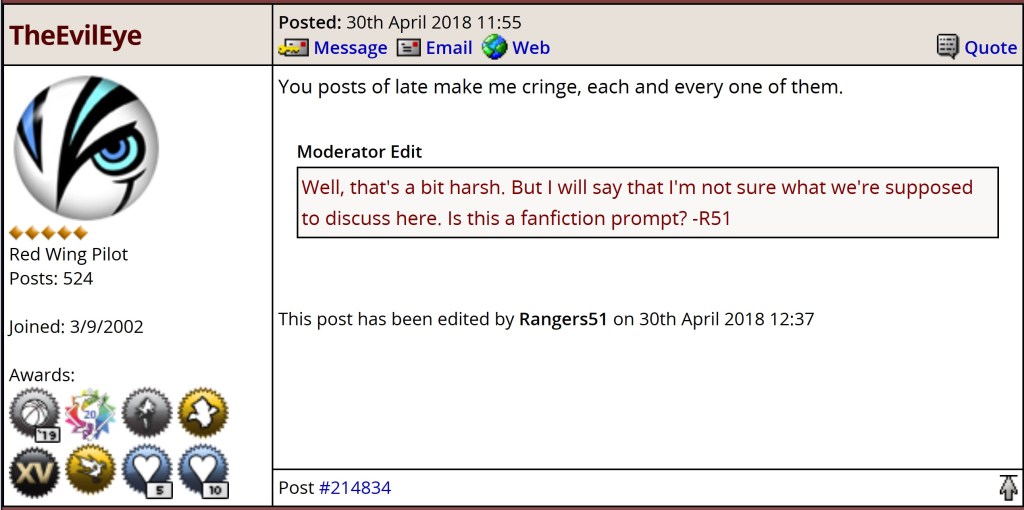

In these communications, the genre expectation is not for perfect grammar or spelling (as in above example). Brevity is a central component; the majority of posts are 1-2 sentences. Often, users include signatures below their posts, usually aphorisms from characters in other video games, pieces of popular internet culture, or links to websites or social media. There are also the inclusion of memes or images from popular culture, such as the Simpsons. In this example, we see a member who has had a message blocked for violating genre norms and critiqued for not staying within the genre’s topic range:

The specific Lexis is related to the game itself. For someone familiar with video games, especially role-playing fantasy games, this lexis isn’t indecipherable. But to someone with no knowledge, the best one might do would be to identify which are verbs and which are nouns, and that they’re being used to describe something in the gameplay itself:

Further, specific references to the characters and story of the game would be “puzzling” to outsiders; this is another marker that this is a discourse community.

And as mentioned in the intro, though difficult to put precisely, Caves of Narshe appears to have had a max of 100-300 people who are active members, mostly during 2000-2010.

So this explains how it fits John Swales’ criteria, but what makes it stand out compared to other discourse communities that can be found online?

First, is the impressive amount of content and detail. It shows a real dedicated fandom, and it appears relatively popular because of the utility of the information on the site. I can testify that it certainly improved the enjoyment of the game for me, and gave me a new level of appreciation for the creators of the game, and the dedication of the site’s contributors. However, like most digital discourse communities, it is not without its flaws or conflicts.

The second most interesting elements of Caves of Narshe are that it conforms to cliché stereotypes about video game players (especially those that play fantasy games). Many of the most prolific commenters in the message boards, and the authors of the walkthrough, indulge in juvenile misogynistic humor, though there are indications that they are adults, and quite possible successful ones.

This appears in three forms. One, occasional sexual fantasies or lurid descriptions of the games’ female characters, two, via references to negative stereotypes against women, and three, in an assumption that the audience are all male, who share a similar mindset. A few brief examples from the walkthrough and one of the message boards:

It should be pointed out that these instances are rare (I could only find a half dozen in the entirety of the walkthrough, and only a few in the message boards). Further, there is push pack by (presumably female) members against this, as well as acknowledgement that the game itself in some ways promotes a sexist worldview. For example, a post in the same feed as the last one above:

The third element that is notable about Caves of Narshe, compared to other online discourse communities, is that it has become both an artifact of an older internet culture, as well as of a sexist culture that was in some respects much tamer and less offensive than that found in internet culture today. The website is like an archive of the interactions of a middle-age players, who first experienced the game as teenagers, and haven’t moved on from fandom. Many consumers of internet culture have left message boards, blog posts, and long, wordy walkthroughs. Today, it is much more likely that someone would watch a walkthrough on YouTube, or watch or look at video or images related to the game. Certainly, message boards are still used, but not to the extent of the internet pre-smartphone era.

The final standout is that by todays’ post-Gamergate, post-MAGA world, the sexism on the site seems trivial and hardly noteworthy. It feels much more like the kind of sexism 15-year-old boys would concoct in the mid-1990’s, before the internet was the main creator of culture. In that sense, it is especially strange: relatively harmless, but neither cute nor funny; more an indication that the internet has pushed extremes in every sphere of our cultural life. Instead of jokes about nudity or women as bad drivers, we’ve moved to death threats, rape threats, doxing and swatting. In the end, it leaves us with perhaps two different feelings:

For some, a bit of nostalgia, a hankering to return the internet to a place where people could connect over whatever hobby they were into, without the threat of attack or being canceled. For others, its an artifact of where we will never return to, like old TV reruns. It is a place not nearly entertaining enough, or extreme enough, or fast-pasted enough for the internet of the future. And for better or worse, this may be all too true.